I can almost hear the guttural crackle of passion in Jesus’s voice as he says, “Open your eyes and take a good look at what’s right in front of you!” His eyes are aflame with a joyous secret that we had not realized before. “These fields are ripe! It’s harvest time!”

A thin layer of sunlight sits atop the crisp tips of cumulous clouds above the Galilean. Beads of perspiration gather on his forehead, as the canvas of the sky bursts and shifts in slow motion. There is a high contrast, heavy color saturation, and Instagram-esque focal blur on everything but the face of the Savior, pushing the scenery into the distance, pulling his expression closer toward the viewer.

Suddenly, I respond with the disciples. My earth-drawn brow lifts, and I raise my gaze to the level of the horizon opposite Jesus.

“Oh my God! How could I have overlooked this once again?”

———

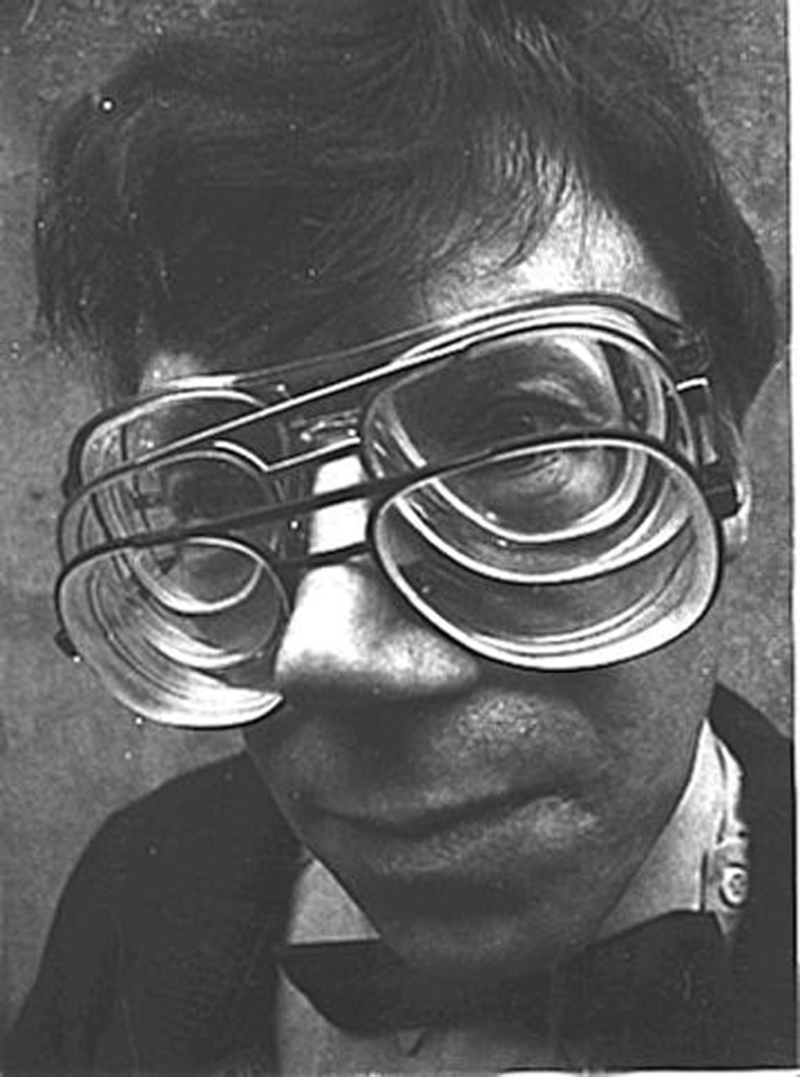

I have an astigmatism in my left eye, and the onset of Keratoconus. The farther the object, the greater the likeliness of double vision.

I am nearsighted. I have myopia.

But the physical condition of myopia is not my only problem. Sometimes I get lost in the canvas.

I cannot see the beauty of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence in Van Gogh’s Starry Night. I become enamored in the swirly globs of oil paint. I cannot see the overall details of shadows and motion in Rembrandt’s colossal The Night Watch. I am fixated on lieutenant Willem van Ruytenburch’s beige hat. I struggle to comprehend God’s rendition of the universe and all it’s nuances. I squint to see beyond the Milky Way, the earth, my own geometric coordinates.

I ludicrously become the focal point of the universe and all its macro realities.

I ludicrously become the focal point of the universe and all its macro realities.

———

I live in Asia, and am daily in contact with the juxtapositions of wealth and poverty, the sharp contrasts of hope and desperation.

I have shared meals of grub worms and rice wine in the huts of the poorest of the poor tribal people groups on the borders of China and Myanmar. I have smiled at the sad faces of child beggars outside my taxi in Manila. I have kissed wide-eyed Liberian orphans in the outskirts of Monrovia.

These experiences should have brought me to a place beyond myself—a new global coordinate of empathy and compassion. And they have, to a degree. But when I return to the comfort of my 450 square foot apartment of Cubao, I am again riveted on my own concerns, both great and infinitesimal.

“Then Jesus made a circuit of all the towns and villages. He taught in their meeting places, reported kingdom news, and healed their diseased bodies, healed their bruised and hurt lives. When he looked out over the crowds, his heart broke. So confused and aimless they were, like sheep with no shepherd. ‘What a huge harvest!’ he said to his disciples. ‘How few workers! On your knees and pray for harvest hands!'”

C.S. Lewis realized that a little bit of myopia occurs in all of us. “There exists in every church something that sooner or later works against the very purpose for which it came into existence. So we must strive very hard, by the grace of God, to keep the church focused on the mission that Christ originally gave it.”

“There exists in every church something that sooner or later works against the very purpose for which it came into existence. So we must strive very hard, by the grace of God, to keep the church focused on the mission that Christ originally gave it.”

I reach for my glasses. I have been trying to read these situations with strained eyes, and should have been viewing life through the lenses Dr. Bundy prescribed for me. I see much clearer through the convex intended for my eyes.

Alan Hirsch reminds me that “what [is] lacking is an overarching perspective that takes into account a more global and regional view of strategic issues relating to mission.”

Finally, I am able to say something like, “I am amazed at how all the infinitesimal aspects of life come together to make such an incredible symphony. Mind you, I am not always this introspective and cognitive. The present details of my life have just brought this epiphany.”

And I recall Brennan Manning’s contemplation: “[Christ] ends our indecision and liberates us from the oppression of false deadlines and myopic vision.”

“[Christ] ends our indecision and liberates us from the oppression of false deadlines and myopic vision.”

Jesus is still gazing at the fields behind me. I turn to take in the landscape. The harvest is indeed ripe with white tips of wind-blown wheat. I pause for a moment, hear the Savior’s steady breathing behind me, reach for my plough, and take another step toward the field.